Yes, It is So Easily Worn

I came across Jim O'Rourke by way of Eureka. Not the song, but the film by Aoyama Shinji. My memory is fogged up; I can't tell if it was in the dying years of high school or in the middle doldrums of college. I wasn't much of a movie guy then, at least, less so than I am now. I was still in the grips of my Caufield era, so this must have been near the start of nurturing a love for the medium. The blockbusters weren't doing it for me, and the idea of going out to the theaters felt like a hassle. (I have a little more appreciation for going out to see flicks on the big(ger) screen, but in the comfort of home, alone, is still my preferred environment). Most embarrassingly, I wanted to watch acclaimed and obscure and out-there films, specifically Japanese ones (or at least, not American nor Indian). The embarrassing part isn't what was desired, but the why behind it: an urge to come across as special, to be made special, a visionary, an egotistical compulsion to trawl the (supposedly) niche in hopes of finding that elusive, never-before-seen "answer" - only granted to me because who else could think of unraveling the mystery of connection the way I could. How pretentious. How pathetic. We are still reeling from the effects of this sciolism.

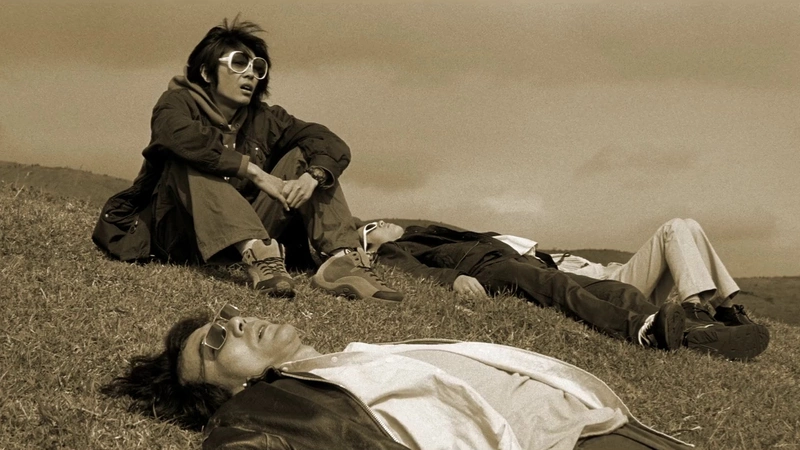

Back to Eureka, the film. I remember the family room of my parents' house, a late night made later still with a runtime brushing close to 4 hours. A movie found via a haphazard Google search for long, critically acclaimed, Japanese films. Maybe Sono's Love Exposure was seen a couple weeks before or after (a movie I'm ambivalent about at best to this day). Miyazaki Kozue holding the polaroid camera straight at the audience, motionless. Yakusho Koji before I really knew who he was. That moment when color seeps past the sepia and washes into the seaside. How does one live? How does one continue on? The sort of questions that keep you up at night at that age (right there's proof, if any, that no maturation has occurred on my side since). And of course, something else to keep your mind trained on your heart: Jim O'Rourke, a ghost wafting in from the radio.

Searching out Eureka, the album, wasn't immediate. It might have been a year since watching the film. I don't think I even thought to put two and two together until I had seen the album mentioned here and there on the internet. One look at the cover was enough to pique my interest: puerile white against fleshy pink against fluorescent magenta blush, whimsical, deranged, with a tinge of a commonplace longing. (A side note: only now am I finding out the artist, Tomozawa Mimiyo, was a mangaka who cut her teeth with publishing in Garo, a storied alternative/avant-garde manga magazine. Just as intriguing, she was involved in a band, Risu, with musician Fukuma Misa — would love to sample some sounds from that effort.) Imagine my surprise finding out the title is a tip o' the hat to a different film called Eureka, a psychological drama from '83 by Nicolas Roeg. (I've yet to watch that joint so couldn't say what's the throughline, if any.) I can't put my finger on exactly why, but it all fits together, the cover art, the title, the nebulous movie reference, and, especially, the sound.

The album starts with a cover of Ivor Cutler's “Woman of the World.” The Fahey-like fingerpicking previously at the fore in the preceding EP, Halfway to a Threeway, buttresses the mantra as chamber orchestrations lift and lilt with it. If there is bombast, it's of an ethereal quality; the album traffics more so in the sounds of a porch fashioned into a makeshift cocktail bar. There's the obvious Bacharachian influences (hard to miss when there's a cover of the Bacharach classic, “Something Big”), but my mind also drifts to Van Dyke Parks' Song Cycle. The soundstage is lush and expansive, with special care given to the dynamics, and various pop traditions meld together alongside a dash of the modern via electronic/tape manipulations. There's the bossa nova tinged rhythm and guitar playing on “Something Big”; the steel drum calypso that drifts in and out on “Through the Night Softly” as well as the gospel-inflected organ and keys; the jazzy piano plonks on “Please Patronize our Sponsor” that gives way to folksy Americana in the company of some sawed strings and brass blows; the chamber folk meets electroacoustic improv of the title track, “Eureka”. Etcetera, etcetera.

So what to pair with the cozy and comforting compositions besides some seemingly misanthropic lyrics? I say seemingly not because they aren't, but because they're sung so sweetly that it's hard to not see them as cheeky and irreverent. Is the arc of his ire pointed outwards or inwards? There's the declaration that starts off “Ghost Ship in a Storm” — “nothing makes me / want to disappear / as when someone opens their mouth” — harrumphing at the minutiae of life lived amongst others. And yet, it is others with agency — the car that careens into him, the wet cement that materializes beneath his bike tires, the obligation of rent to pay that presses down on his mind. The speaker is turned into the indeterminable — “I'm not there / like a ghost ship in a storm” — a specter and a spectator. That all jibes with a misanthropic angle, even despite (or perhaps because of) the comedy of the scenarios — so where's the rub? I'd venture it's a question of dealing with ennui, not of a distaste for others. And it's a question, not a statement; here is no simple resignation, but an active grappling with the sentiment. “Something Big” hints at that wrestling: the wistful desire to be “the man I'm not” is floated on the airwaves, wistful in the way “a grain of sand / wants to be / a rolling stone”. In it too is the idea of being in communion with others — “after a taking, take up a giving” — which cuts against a primarily misanthropic reading. We see the struggle again in the title track, as O'Rourke caustically sings “you're thinking on your feet / while sitting there on your ass”. This could be a bladed statement pointed at the world/audience — and perhaps it is, but it's also pointed back at the singer. The desire is there, but the transmutation of it into action isn't. And likewise, the idea that life is not simply being but being with is echoed in the statement “a seed don't make a tree / without a servant who waters the grass.” There's a strain of internalized ambivalence suffusing the lyrics, exploding in the (non-Japanese version) final track. It's a suicide note of sorts — or perhaps, a request to be relieved — but not without some churn. An ardent wish to be somewhere where the din of the radio can drown out the traffic of thought, a hope to not wake, and yet there is the rueful proclamation “that one of life's greatest sins / is that you're over before it begins”, which hints at a desire to truly live — a desire that echoes the sentiment of the grain of sand alluded to in “Something Big”. But there is still a note of resignation as O'Rourke makes a callback to a Gastr Del Sol track in which he sang, “Mouth Canyon”. (Gastr Del Sol being the band he was in with David Grubbs prior to his solo efforts). I'm not so sure how to read the reference: O'Rourke has mentioned in a 1998 interview with Josh Ronsen that he found his singing to be pathetic on the track so perhaps that's why the canyon isn't “very much to see” — then again, O'Rourke also seems to be quite self-deprecative of his ability when looking at other interviews (hell, back in '09, in an interview with the AV Club, he's pretty adamant that Eureka is a complete failure, sonically and lyrically — we know where I stand on that). What does scan to me, at least in my reading of the album, is that the refrain in “Mouth Canyon” — “transparent is ok” — is challenged, that in fact transparency is not ok, that it is not sufficient to be a “ghost ship in a storm”. Therein lies the angst: desire and inability. Transparency is not ok, sitting on your ass is not ok — and yet, not chasing after something big is also not ok. Which is why he only comes to leave.

I'd be painting an incomplete picture if we left the lyrics here. It's not all one-note doom and gloom. The beauty in the incongruencies isn't just in the intersection of cover art, sound, and lyrics, but also nested within the words themselves. More than any sense of despair or struggle, the most striking quality of the lyrics is that O'Rourke is damn funny! There's a delightful absurdity in zoning in on a wedding cake smashed into your face post getting hit by a car, emphasizing the red of cherries instead of blood, as there is in imagining wet cement as quicksand and proclaiming the last thought to enter your mind is if you paid your rent or not. Or take the way he mocks those who think but don't do — “fresh crease in your shirt / no stain of sweat on your back” — filled with invective but also a lightness that invites a smirk (as someone worthy of such jeers, a smirk pointed back at myself). Or even the sly way he leverages segmentation of lines to hint at a male fantasy of a place where the women have nothing on before turning the sentence on its head by revealing they have nothing on but the radio — sure to induce a giggle in the more than slightly immature (a.k.a. me). This is where the irreverence, the cheekiness, really comes to the fore — not quite gallows humor, but a sister to it. “Segmentation” might be the key word here. The way the lines are cut, the way the images received from the lyrics transform when taken whole or at one end or the other, is a microcosm of the relationship between the other, disparate elements of the work. The cover art, the music, and lyrical content and form work as segmented elements of each other, where the space between them operates as a ghostly gear whirring them into a harmonic incongruence.

The picture is still incomplete. When I think of the track that most moves me, the words that arrest my heart, it isn't the one used in Aoyama's film. Shakers and tape fuzz open the stage before ponderous strings and horns sprout in the bed. An inquisitive bassline saunters in alongside hanging synth chords, and a laconic guitar plucks and strums before giving way to electro-acoustic manipulations that bubble in and out like waves. If it wasn't for the title, you'd think it's announcing the beginning of the world. But it's not. Suddenly, midway through, the synth begins a simple, but haunting, descending melody. The shakers and the electronics recede. An upright bass thunks and creaks in time. And, now, he sings. There's something oh so tender yet despairing about it. Something cutting in the way the questions are pronounced, as if they're accusations pointed at the jugular, and yet, with a serene gentleness, as if they are the only truly important questions to ask. And that penultimate question! O'Rourke, rising in a chorus with himself: “Is your smile so easily worn? / Worn Away”. It kills me every time. “A Movie on the Way Down” — couldn't call it anything but. There's a certain hilarity in plopping a track titled like that in the middle of an album, one that perfectly encapsulates the ethos of Eureka, where the depressing is buddy-buddy with the comedic. Like the best of inside jokes, the ones where you're the only party privy, the ones you keep locked away and fold out now and then to invoke a soundless snicker and a forlorn sigh.

You know, I don't think that track would have been out of place at all if it was the one used instead of the title one in Aoyama's film, leaking out of the radio and washing into the seaside as the movie slips into its denouement. I wonder how the hue of the film would have changed? Or the hue of my heart? What other avenues would I have taken to get here, if at all? I think of the mystery of connection again. How did those two get in cahoots? O'Rourke's been known to be quite the movie buff (see: above, and less snarky, his interview with Kurosawa Kiyoshi in BOMB Magazine), and has done more than his fair share of soundtrack work over the years. Though not for this film — it was Aoyama in tandem with Yamada Isao who composed the OST. Not only could he perform, but he certainly had a taste for music, rubbing elbows with some of the giants in the Japanese avant-garde scene — Yoshihide Otomo and Phew to name a couple. (An interesting note: Aoyama had mentioned that a particular bit of inspiration for the film was Sonic Youth's Daydream Nation, a band O'Rourke has collaborated with as a fellow musician and producer). Perhaps he found the album by chance while spinning up his script. Or maybe Yoshihide turned him onto it (or, possibly, he turned Yoshihide onto it via the film: there have been so many wonderful iterations of the song “Eureka” by Yoshihide and his bands over the years). Or maybe, and this is what I'd like to believe, they stumbled into one another over a chance encounter over drinks at some dinky Izakaya. Connections! How wondrous, how unknowable — but also, how certain! — like so many spider threads, thin and invisible from a distance, but oh so resilient, unbreakable even, running the gamut from the material (like their correspondence, like my own vis-a-vis their work) to the immaterial (like their internal feelings, like my own)!

My mind turns to Robert Ashley's “The Park”. That's another connection to add to the web (like I said before, we are still reeling). Specifically, of the two men sitting on a bench at the park, imagined, discussing the division between the permanent and the impermanent. More specifically, of what they have to say about what lies on the permanent side of reality: space, or rather, connections. It is irreducible and non-transitory, and stays as long as one lives, they muse. So what becomes of it after? Aoyama Shinji passed away in 2022. Jim O'Rourke is still alive and is as prolific as ever. And here I am. And here you are. The threads continue to be spun, under auspices of the ghostly and the distant. And under those same auspices, they are transfigured into something close and tender.